TSN in Combination with EtherCAT

TSN is an important building block for convergent communication in flexible production. Mastering and integrating existing field bus technologies such as EtherCAT is an important part of the transition. Let's take stock of what is already possible. This article was first released in Computer&Automation in German.

The globalisation, regionalisation and personalisation of markets have a profound impact on manufacturing companies. Flexibility and changeability are necessary to meet these requirements. Various technologies, paradigms and perspectives are seen as enablers of this flexibility and changeability. These approaches have in common an increasing networking of the systems used in manufacturing. Only if all participating systems have transparent information at all times can flexibility be guaranteed. However, for increasing networking, communication streams from operational technology (OT) and the control levels (IT) must be merged. The Time-Sensitive Network (TSN) enables the coexistence of OT and IT communication streams through the standardisation of a real-time data link layer (layers 1 and 2 of the OSI layer model) by the IEEE. TSN thus makes it possible to maintain the real-time requirements of OT communication while also using the network for IT communication. TSN is therefore considered a key technology for this convergent communication. For many years, the term Industrie 4.0, which was coined at the 2011 Hannover Messe, has been used to describe the work being done to achieve flexibility and changeability using TSN. What has been achieved so far?

TSN as a key technology?

One challenge in the development of TSN standardisation is the time required. This has led to the fact that it is only recently that product-ready technologies have become available that support the TSN standards that are important for automation. Another challenge is that TSN only covers the lower communication layers and the higher layers are implementation-specific. OPC UA with the pub/sub extension for real-time communication is one of the most promising candidates for filling these layers on a greenfield site. However, the transition to new technologies will not be seamless due to complexity, unresolved dependencies and network configuration. Interoperability of existing technologies is therefore an important step towards convergent communication based on TSN. This is why many fieldbuses are based on compatibility and use TSN on the lower two layers; examples include EtherCAT and Profinet. But to what extent can fieldbuses actually be used in a TSN network in a convergent way?

The candidate: EtherCAT

EtherCAT is an established field bus that is enjoying growing popularity, which is partly due to its real-time performance, which also meets critical time requirements such as motion, but on the other hand it is also open and a large number of software stacks are available for it. This makes EtherCAT an ideal candidate for convergent communication via TSN.

An EtherCAT network consists of a single master and multiple slaves. The physical wiring can be implemented as a combination of star, tree and line topologies. The logical topology is always a ring. The master is the only communication device that sends EtherCAT telegrams. This collective telegram contains the EtherCAT data of all slaves and passes through all communication participants, which receive the output process data, enter the input data and forward the telegram. The telegram is sent back to the master by the last device. In addition to the cyclic process data, acyclic data is also exchanged via mailboxes.

Synchronisation between devices in an EtherCAT network is based on the Distributed Clock (DC) mechanism. The clocks of all DC-capable devices are typically synchronised to the clock of the first DC-capable slave with an accuracy of less than 100 ns. This allows highly precise time stamps to be assigned to recorded data and achieves a synchronisation that is essential for motion control applications.

The convergence project

The analysis and evaluation of the potential for convergence that is already possible was carried out at the ISW using a cloud-based scenario. This scenario is based on the vision of software-defined manufacturing (SDM), which stands for the separation of hardware and software. In the realised scenario, a single IPC controls several machines.

EtherCAT uses broadcast Media Access Control (MAC) addresses to send telegrams to all slaves. Consequently, it is not possible to use the same cable for several EtherCAT networks. Additional mechanisms must be implemented. The EtherCAT Technology Group (ETG) has published the TSN communication profile ETG.1700, which solves this problem by mapping to two unidirectional streams with a defined MAC address. This is implemented by an adaptation layer in the EtherCAT master and in EtherCAT slaves, which is referred to as stream adaptation. The project described here does not use the stream adaptation described in the ETG.1700 profile, but rather several Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) defined in the IEEE 802.1Q standard. This makes it possible to use conventional EtherCAT bus couplers instead of specialised TSN-capable couplers.

Now, although the data traffic of several EtherCAT networks can flow through the same cable, the synchronisation of the clocks still needs to be defined. TSN provides for synchronisation of all network devices to a global clock using the Precision Time Protocol (PTP). This is therefore a different technology from the DC mechanism of EtherCAT. This can be solved in a brownfield-friendly way by using the EtherCAT master as a reference clock in the DC mechanism and synchronising the EtherCAT master to the global TSN time. This procedure is also described in the ETG.1700 profile.

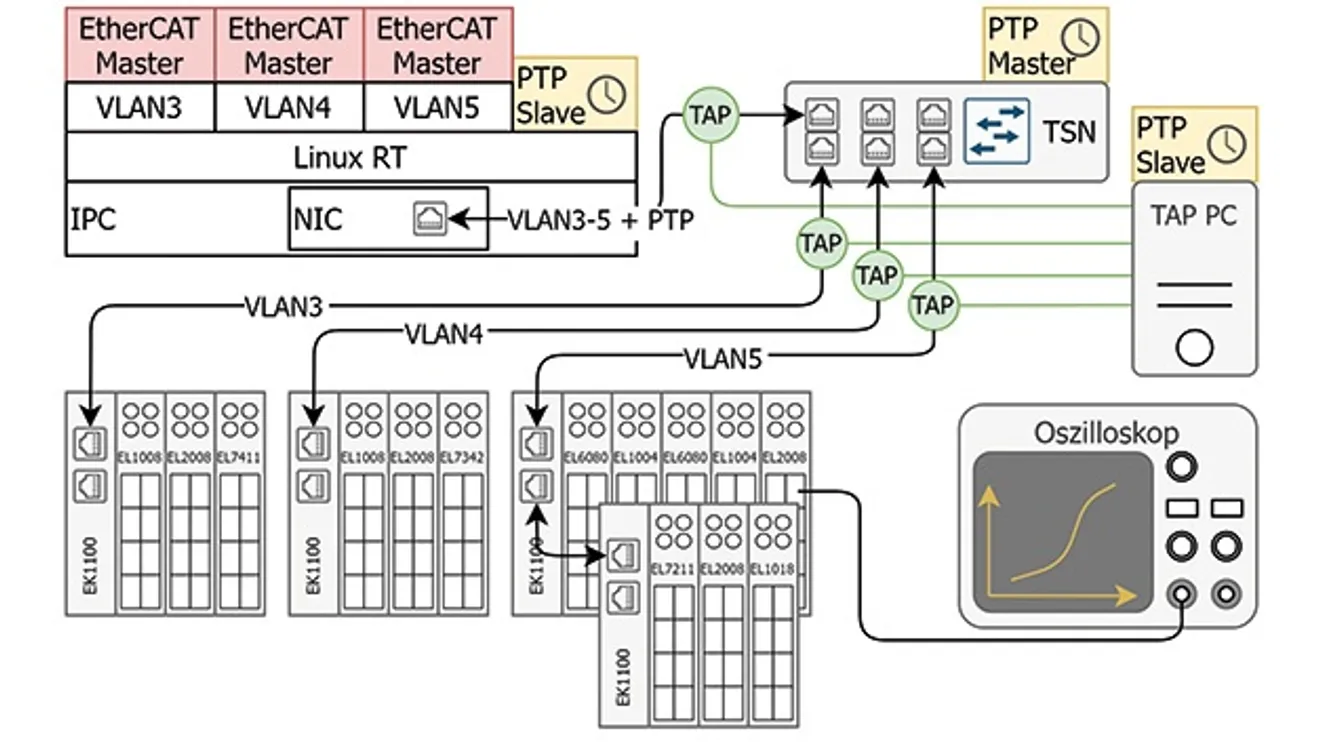

Figure 1: The evaluation method.

Figure 1: The evaluation method.

The structure and the evaluation methods are shown in Figure 1. The IPC and the TSN switch were implemented using Kontron products that are available for purchase. The EtherCAT terminals are from Beckhoff. The DLR libethercat stack is used for the EtherCAT master.

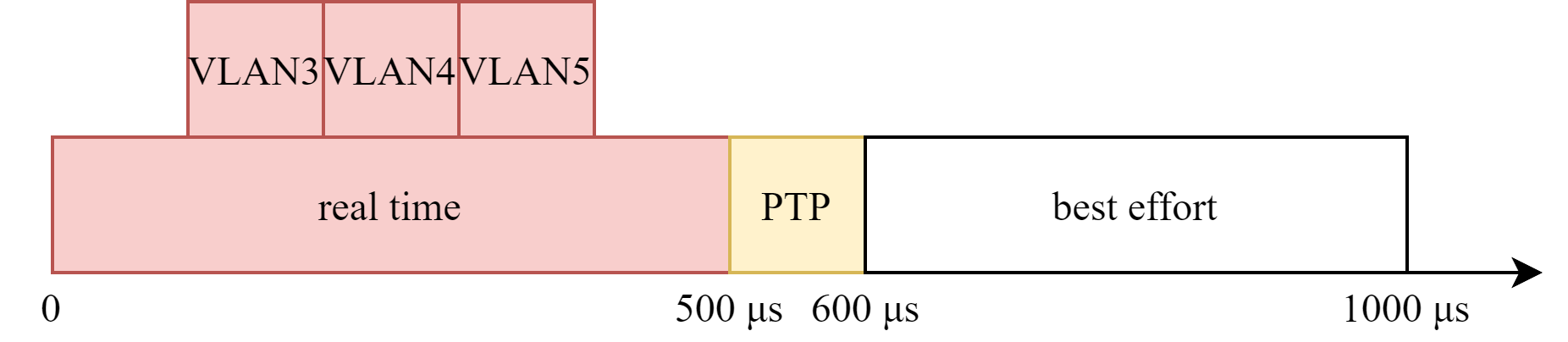

Figure 2: The schedule.

Figure 2: The schedule.

The TSN schedule is implemented as shown in Fig. 2: Three data traffic classes are used; the three EtherCAT networks are scheduled in three separate time slots. This means that the EtherCAT masters send the cyclic process data packets in their time slots.

The analysis method

Two measurement methods are used to evaluate the real-time performance of the system. First, the data traffic of each cable is monitored and measured using a network test access point (TAP) that has constant and deterministic monitoring latency. The TAP is used to mirror the data traffic, which is then analysed in a separate evaluation PC. The clocks of this PC are synchronised with the TSN time. In this way, the latency times of network packets can be determined exactly according to the TSN time domain. In addition, an EtherCAT slave with a digital output generates a periodic square-wave signal by toggling the output in each cycle. This signal is then measured with an oscilloscope and the signal jitter is determined.

The results

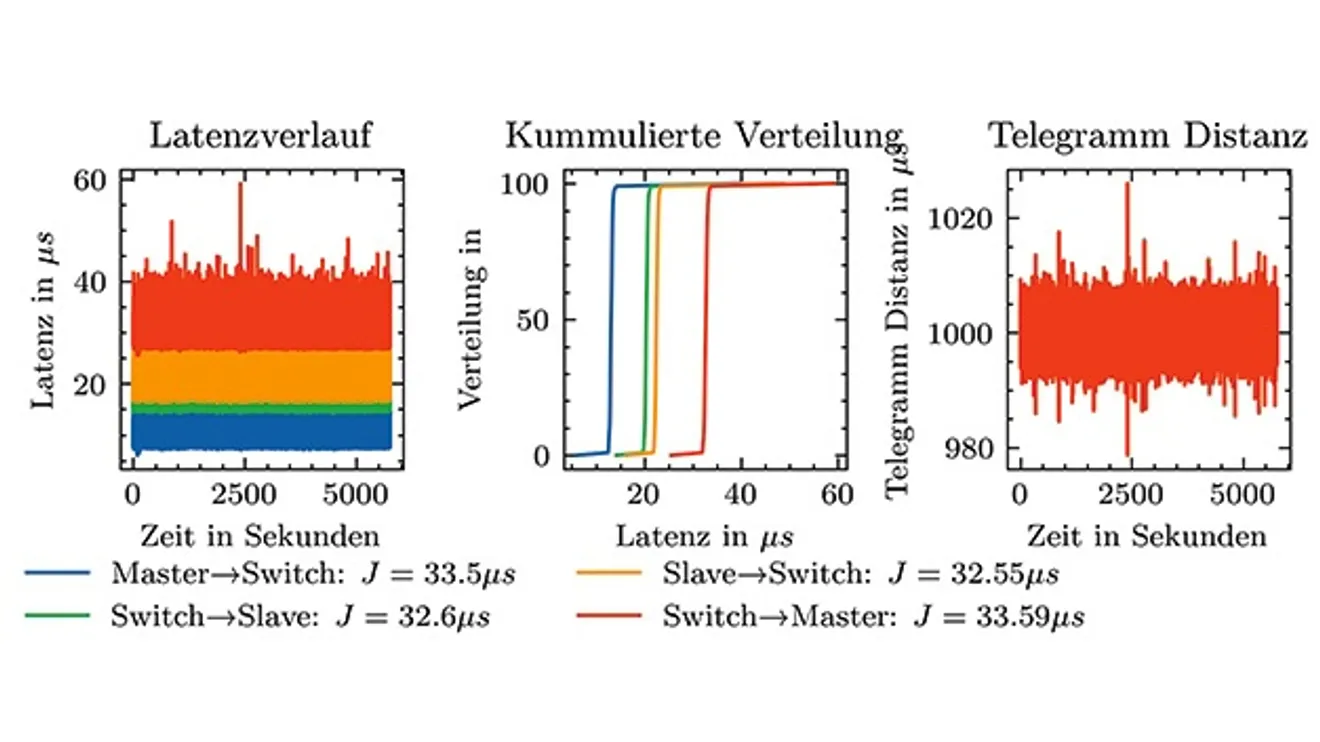

The latencies are determined on the basis of the scheduled transmission times of the cyclic process data telegrams. They result from the difference between the time of arrival of a packet at the TAP and the scheduled transmission time. The TAP monitors the two packet directions separately. Therefore, the four monitoring points Master->Switch, Switch->Slave, Slave->Switch and Switch->Master are used. Two different methods are used to comply with the scheduled transmission times on a Linux RT system.

Figure 3: The results.

Figure 3: The results.

First, a classic RAW_SOCKET is used (Figure 3). A packet jitter of 30 µs can be measured, caused by the Linux kernel network stack. The TSN switch does not add any measurable jitter. The jitter can be reduced using the Linux kernel's SO_TXTIME function. This involves passing the planned transmission time to the network card, which then uses this time to send the packet at the planned moment. The measurements show that the number of outliers decreases and the jitter drops slightly. However, no packet loss based on the telegram distance can be observed.

The measurements with the oscilloscope are carried out for one minute (Figure 5). A time span without packet loss is selected for SO_TXTIME. The jitter when using RAW_SOCKET is approximately 7 µs, which is slightly higher than that of SO_TXTIME, which is approximately 2 µs. The signal jitter is thus lower than the telegram jitter of the periodic EtherCAT packet, which is due to the equalisation of the DC mechanism.

The take-away

The question posed at the beginning can be answered as follows: The EtherCAT field bus can already be used in a convergent manner in a TSN network. However, the Linux network stack causes a jitter of around 30 µs on the test system used. Another Linux network function is the eXpress Data Path (XDP), which enables the sending and receiving of packets while bypassing the kernel network stack and reducing jitter. Currently, SO_TXTIME cannot be used in combination with XDP, but there are already some patches that try to bring this function into the mainline Linux. XDP is therefore an open topic for future work, which will be addressed by us.

It is possible to tunnel EtherCAT through TSN based on VLANs and to use existing EtherCAT couplers. A detailed analysis of the time synchronisation shows that it is possible to synchronise EtherCAT slaves with the DC via the EtherCAT master in a TSN network. It has also been demonstrated that the presented architecture can be used to operate multiple EtherCAT networks over a single cable.

Bring Convergent TSN + EtherCAT Networks to Your Factory

If you’re looking to combine the real-time performance of EtherCAT with the flexibility of TSN, our insights and implementations can help you take the next step. Learn how to operate multiple EtherCAT networks over a single cable, synchronize devices accurately, and minimize jitter — all while leveraging standard hardware and brownfield-friendly approaches. Whether you’re designing next-generation industrial networks, implementing software-defined manufacturing, or exploring TSN-based automation, we’re ready to share our experience and solutions.

Contact us to discuss collaboration, pilot projects, or consulting opportunities — and start building the factory network of the future today.